Bianca Raby, Founder/CEO, and Jay McGrane, K-12 Educator and Researcher discuss the microlearning...

What google can teach educators about assessing innovation

Nearly everyone wants to work at Google. Free food, a free gym, shuttles to and from work, and, of course, an excellent salary (paid for with mind-boggling innovation developed by happy talent). But assessing innovation...

Has the tech giant cracked the code on innovation? And if so, what can educators learn from them?

Educators hope so because Australian students and employees desperately need to learn how to become more creative (or in business-speak: innovative). The Foundation for Young Australians’ research revealed the demand for creativity has risen by 65% from 2015-2017.

If they have cracked the code on creativity, Google attributes it to their 9 Principles of Innovation. Of course, these Principles apply to businesses too, so how can instructional designers use Google’s 9 Principles to encourage innovation in their online courses while also assessing student performance?

This blog post will distil a few of these Principles into three best practices for teaching creativity in online settings.

Fostering divergent thinking

Google famously encourages employees to use 20% of their work hours on passion projects.

Gopi Kallayil, Google’s Chief social evangelist, promises, “They will delight you with their creativity.”

In a learning culture where large portions of online courses exist solely to ensure compliance, spending 20% of your learner’s time on a passion project sounds ludicrous. Because it is. However will you justify your L&D budget if your learners aren’t meeting business objectives?

So what can instructional designers learn from this policy?

1) People develop better ideas when they follow their passions.

Takeaway for instruction: Build choice into assessments. Of course, learners still use the course material, but they might be able to show their learning in different ways, such as through video rather than text.

2) Creativity requires time.

Takeaway for instruction: Give learners time to perform creative thinking tasks throughout the course.

Psychologists often measure creativity by administering divergent thinking tasks. Divergent thinking simply means coming up with a variety of solutions for the problem. By including a brainstorming or planning section, instructional designers can help learners generate more creative solutions. Technology takes mind-mapping to a whole new level. Here’s a post by Productivity Land reviewing various software on the market to get your learners mapping like pros and another in-depth review of XMind 2020 by SoftwareHow based on real testing and results.

But is mind-mapping and brainstorming enough?

Google doesn’t think so.

Instead, they also encourage their engineers to magnify their solutions by 10x, rather than just 10% because they’re aiming for revolutionary change.

Fortunately, learners don’t need to create everything they dream up; otherwise, organisations would quickly run out of money. But by moving the standard from a few bubbles filled in to a focus on true revolutionary change, instructors will encourage more creativity.

Typically, people live up the standards set to them so if instructors set the bar higher on creativity, they’ll receive more creative responses.

Designing meaningful assessment tasks

Google’s ninth, and most important principle, according to Kallayil is a “mission that matters.”

No one wants to perform busy work. Everyone wants to believe their contribution matters, but often quizzes and tests just check the completion box.

Instructional designers need to make sure their assessments matter. But how?

By giving learners project-based assessments, instructional designers can ask them to solve problems relating to their organisation using their new knowledge.

But creating authentic project-based assessments is difficult. Design thinking provides a great template for instructional designers and learners to follow in both designing and implementing a project-based assessment.

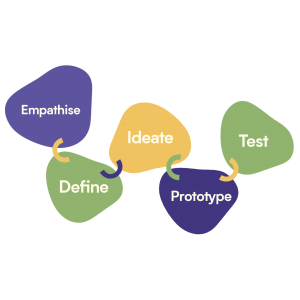

This diagram shows the five steps in Design Thinking: 1) Empathise, 2) Define, 3) Ideate, 4) Prototype and 5) Test.

Design thinking promises that learners will challenge their assumptions, think outside the box and create innovative solutions. But the best part, for instructional designers, is that it gives their learners a defined process to follow.

Proponents of design thinking consider it a third way between intuitive methods of creativity and scientific approaches. Design thinking incorporates the human by empathising with the user at the beginning, but takes a more scientific approach by cycling through testing prototypes. Finally, it can be labelled a cycle since designers often return to generate new ideas or even new definitions of the problem after completing testing.

Since design thinking starts by focusing on the human aspect, anybody can use it to solve problems. Writers can empathise with their audience to define their problems and eventually create content to solve those problems. Basically, it drives all businesses to serve others better.

If you want to learn more about design thinking, IDEO is the organisation to check out.

Seeing through the users' eyes

Google attributes its success to its second Principle of Innovation: focus on the user.

The culture of compliance at all levels of learning takes the user out of the equation. In fact the test-taker BECOMES the user. Furthermore, schools and universities now refer to students as clients, which makes it clear that the student is the user in these institutions.

Assessments following the design thinking process will help learners to focus on the user by placing empathy as the first phase. However, instructional designers need to create authentic projects with end-users to make this Principle of Innovation workable in an online course setting. Learners need to be empowered to create products or services to solve authentic problems. These problems don’t need to be earth-shattering, but they need to have real people using them on the other end, even if it’s just creating solutions for each other.

When designers empathise with users to discover their pain points, the process becomes user-centred, rather than product or learning outcome centred. Fortunately, the digital world provides access to thousands of real people complaining about their problems. Learners might be able to turn up interesting issues simply by trolling a few forums. Or, they could interact with someone via a social media platform to discover their problem. The online world truly lowers the barrier between user and creator.

A blog post, by Social Innovation, offers 8 concrete suggestions on other ways to try and see the problem from a different point of view that instructional designers can transform into exercises to help learners see from an issue differently.

And if all else fails, become the user of your own product. Once you try out the product, you’ll probably have an opinion on how to change it.

So how do I assess it all?

Innovative or creative solutions don’t lend themselves well to testing scenarios.

Google’s Principles of Innovation aren’t a test with a right answer sitting on the CEO’s desk—they’re a series of processes and states of mind.

Just like Google, instructional designers need to assess the process to begin to measure innovation, not the product. Rubrics provide the ideal assessment tool to begin to show your learner a new way to think. Our post on designing the perfect rubric will help you figure out how to best quantify these more intangible skills.

But without a test, designers will need to become like Google—they’ll need to trust that the process helps our learners learn, not a test.

What do you think? Should learning and development embrace some of these Principles of Innovation? Can we ditch the test in favour of more authentic project-based assessment tools?